The Inframent

RESERACH/PRODUCT / 2020

Download pdf ︎

Collaboration with Lucy Allen

From designfield.studio

By abstracting land information into a sonic landscape, seismic sound instruments encourage visitors to contemplate the mysteries of the wild around them and their presence in it.

Change works slowly but constantly in geology. When we look at a striated canyon wall in the desert, we can see the multicolored strata clearly defined. Each layer of minerals and sediment is a period of time compressed and reformed throughout epochs.

In Yellowstone National Park, the geologic history of the land is less visible, but no less present. Lava flow underground shapes and reshapes the plates above. Seismometers constantly stream out recordings of vibrations in the ground in the form of waves that narrow with stillness and bulge with activity. The vibrations are too slow to hear or feel, but they still shake our bodies imperceptibly.

In Yellowstone National Park, the geologic history of the land is less visible, but no less present. Lava flow underground shapes and reshapes the plates above. Seismometers constantly stream out recordings of vibrations in the ground in the form of waves that narrow with stillness and bulge with activity. The vibrations are too slow to hear or feel, but they still shake our bodies imperceptibly.

John O’Donohue, an Irish philosopher, believes that beauty in a landscape is much more than the physical forms of the land. It is the elemental rhythm of the place. What if park visitors could come into rhythm with the elemental in Yellowstone?

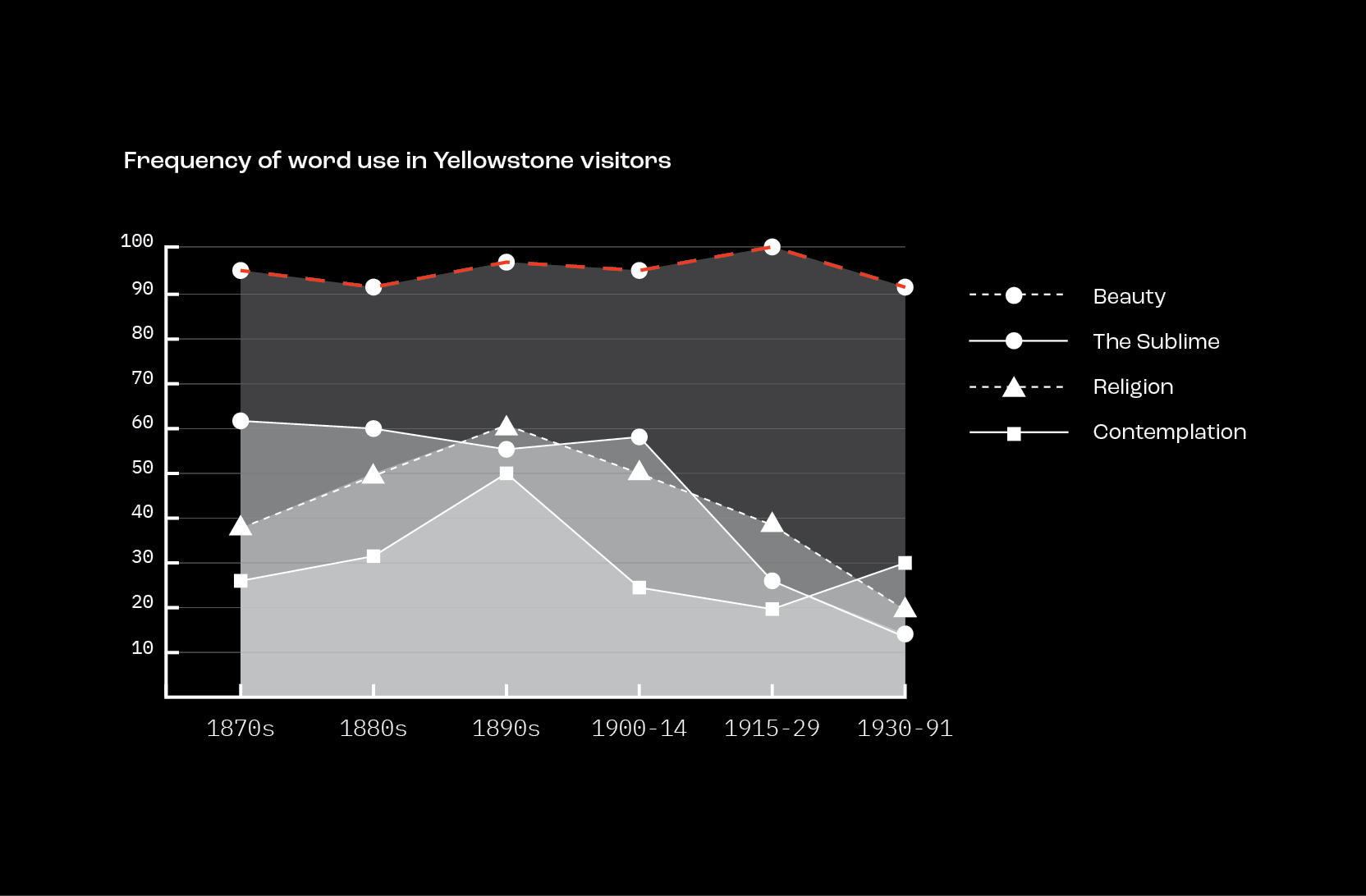

Eco-theologists argue that human spiritual worldviews affect how we interact with and learn about nature. For the last century, mentions of “the sublime” and “religion” in literature about Yellowstone have been declining. By sonifying seismic data of specific locations in Yellowstone, the Inframent creates a sonic landscape that invites visitors to feel the sublime of Yellowstone. Just as geology changes our perception of time by compressing eons of earth history into one canyon wall, sound has the potential to reform time.

Eco-theologists argue that human spiritual worldviews affect how we interact with and learn about nature. For the last century, mentions of “the sublime” and “religion” in literature about Yellowstone have been declining. By sonifying seismic data of specific locations in Yellowstone, the Inframent creates a sonic landscape that invites visitors to feel the sublime of Yellowstone. Just as geology changes our perception of time by compressing eons of earth history into one canyon wall, sound has the potential to reform time.

Context

Only 2% of Yellowstone visitors leave roads or boardwalks, the most heavily trafficked areas of the park. In an effort to ensure visitor safety and the health of the ecosystem, the infrastructure of roads and boardwalks perpetuate a false dichotomy between “human” and “nature”.

Within writings about Yellowstone in the past century, the frequency of the words “religion,” “sublime,” and “contemplation,” have fallen under 30%, while “beauty” remains above 90 percent. (Meyer, 1994)

Social systems exist within ecosystems and are dependent on them (Ostrom, 2009). Visitors to Yellowstone are nested within the ecosystem. However, the problem of accommodating large amounts of visitors has created a park in which visitors feel separate from the ecosystem. Spiritual experiences can help to restore the connection between visitors andthe ecosystem.

National parks are pilgrimage sites that embody the collective myths of American culture. (Ross-Bryant, 2005). Rituals take place at pilgrimage sites and are informed by myths and tradition.

The current Yellowstone rituals reinforce old myths about the park like individualism and the untouched frontier. The Inframent adds a new ritual to the park pilgrimage experience and changes myths about Yellowstone.

The current Yellowstone rituals reinforce old myths about the park like individualism and the untouched frontier. The Inframent adds a new ritual to the park pilgrimage experience and changes myths about Yellowstone.

The Inframent is a platform of sound experiences that take place throughout Yellowstone. The 32 seismometers in the park each produce a unique sound based on nearby seismic activity.

Platform

SEISMIC ORCHESTRATION

Each of the seismometers in YNP monitor a specific area around the most active center, the caldera (University of Utah, 1983). Transmitted by radio waves, the geological network creates a orchestra of seismic activity.

Each of the seismometers in YNP monitor a specific area around the most active center, the caldera (University of Utah, 1983). Transmitted by radio waves, the geological network creates a orchestra of seismic activity.

Locations of recent earthquakes create a map of the activity underground. (ASL, 1990). The seismometers closest to these movements interpret a unique reading of the activity. Looking at the readings as a whole assembles a seismic orchestra.

Visitation

Mammoth Hot Springs is a popular site near Yellowstone’s north entrance. The Inframent would be placed on the Sepulcher Trail near a parking area. The Mammoth installation acts as a gateway from boardwalks and cars to a deeper understanding of the dynamics of Yellowstone’s caldera.

Hoodoo Basin, near Parker Peak, is located on a backcountry trail 17 miles away from the nearest road. The Inframent would be placed next to the trail just before the edge of the basin. At Parker Peak, the Inframent deepens backcountry hikers’ reflection about the landscape they are immersed in.

Instrument

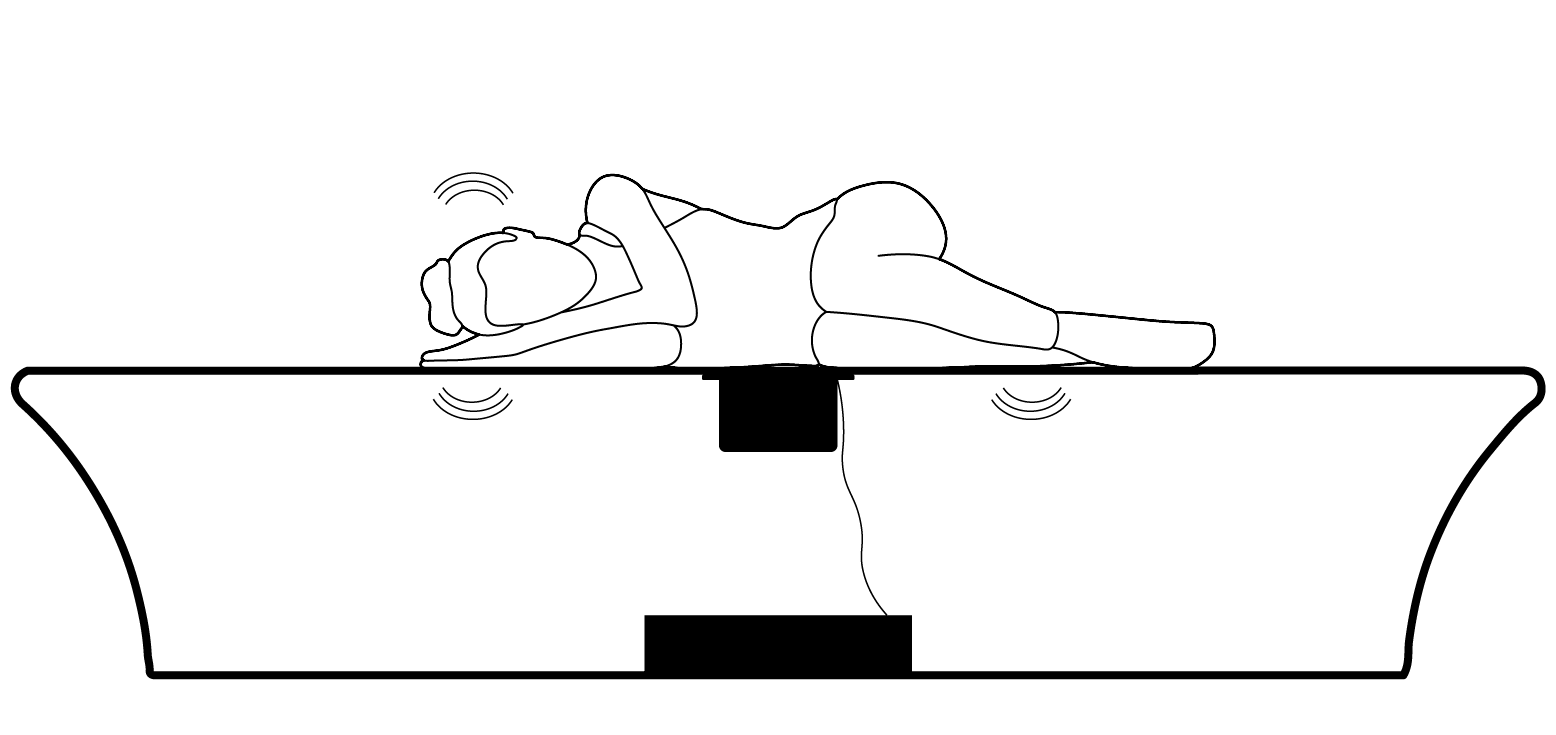

The Inframent invites visitors to fall to the ground and feel a connection to the earth, where the vibrations of the caldera originate. A sacred heartbeat.

The Inframent vibrates a steel shell with the waves of seismic motion, creating sound that is broadcast to Yellowstone visitors.

Data Sourcing

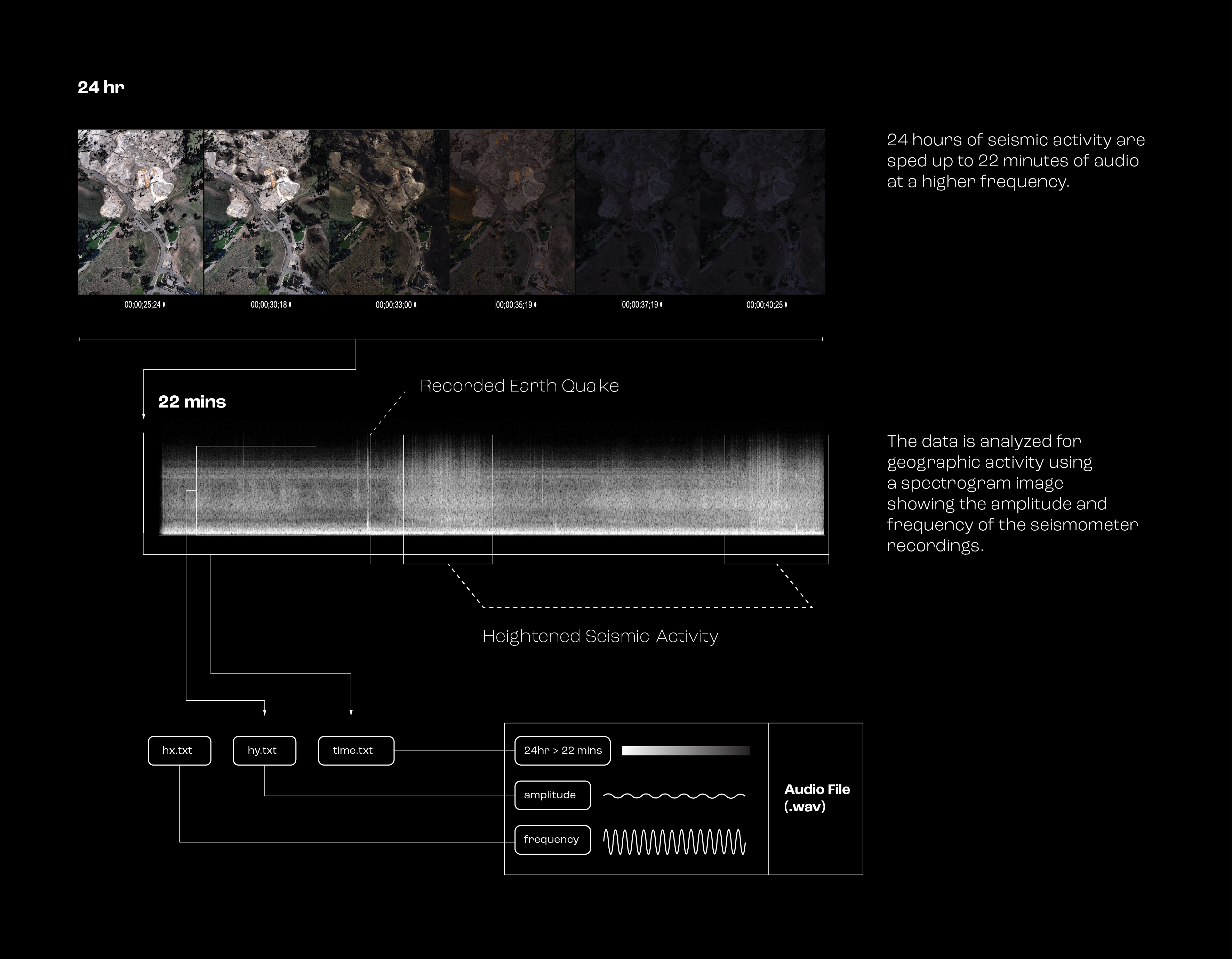

Seismic activity is remotely accessed within 30 minutes of the seismometer recordings. “.Seed” is the standard file type for captured movement. Seed data for the Inframent was accessed through the University of Utah seismometer network courtesy of Jamie Farrell and IRIS.gov.

Seismic activity is remotely accessed within 30 minutes of the seismometer recordings. “.Seed” is the standard file type for captured movement. Seed data for the Inframent was accessed through the University of Utah seismometer network courtesy of Jamie Farrell and IRIS.gov.

Scripting

Using a Mat-Lab script, courtesy of University of Utah geologist Jeff Moore, geographic seed data is translated into text files including the time-code (1:65 ratio), geophone x-height and y-height. Infrasonic sound is stepped up to higher Hz that is audible by the human ear.

Using a Mat-Lab script, courtesy of University of Utah geologist Jeff Moore, geographic seed data is translated into text files including the time-code (1:65 ratio), geophone x-height and y-height. Infrasonic sound is stepped up to higher Hz that is audible by the human ear.

Sound Reverberation

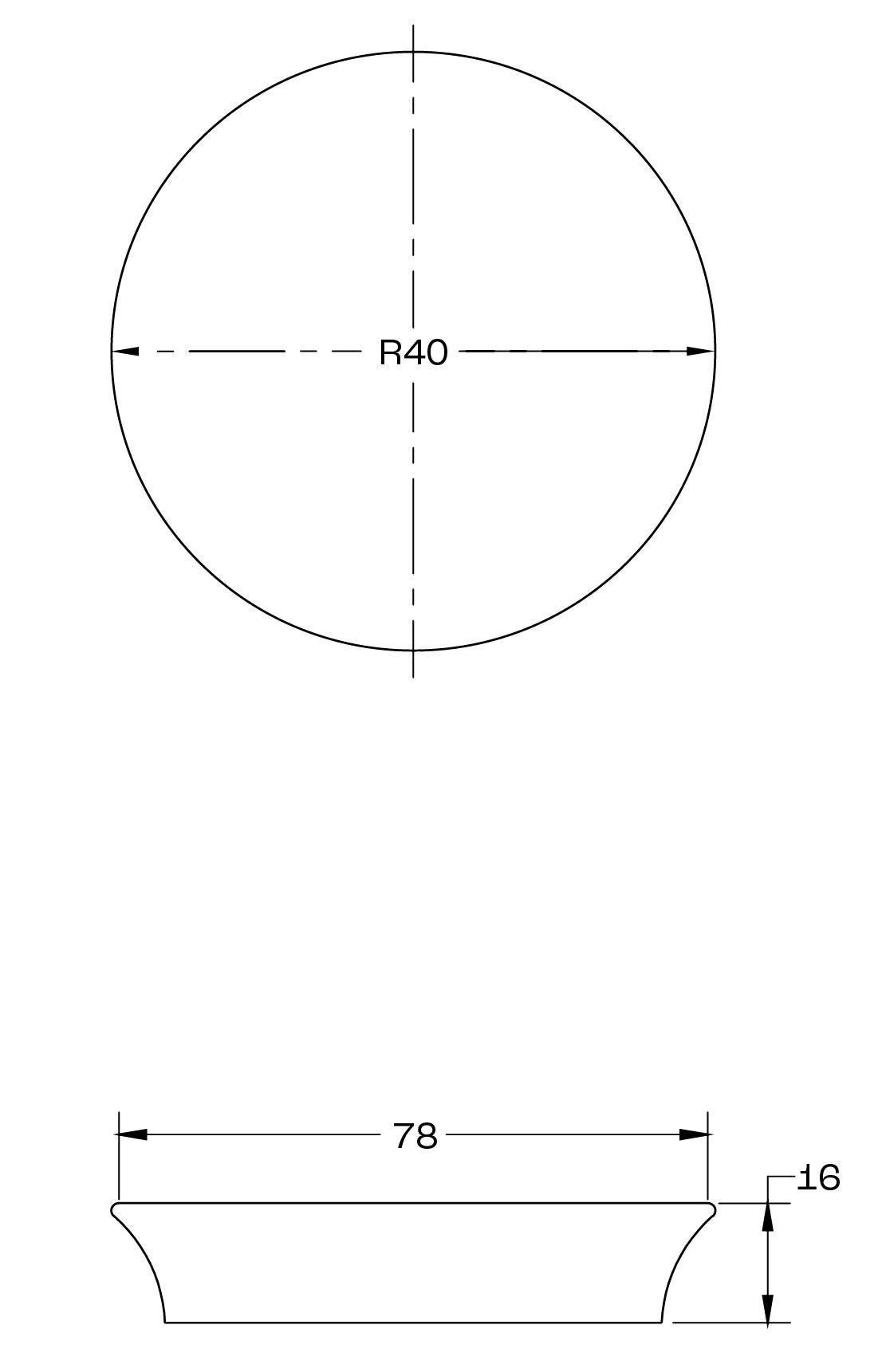

Because of its reverberation wavelength, steel sonifies vibrations at a greater distance. (Fuchs, 2017). At a frequency of 100 Hz, The wavelength through steel completes a distance of 168ft.

Sound Decay

If played at 70 decibels, the sound will exceed outdoor background noise when visitors are within 4 meters of the Inframent.

Because of its reverberation wavelength, steel sonifies vibrations at a greater distance. (Fuchs, 2017). At a frequency of 100 Hz, The wavelength through steel completes a distance of 168ft.

Sound Decay

If played at 70 decibels, the sound will exceed outdoor background noise when visitors are within 4 meters of the Inframent.

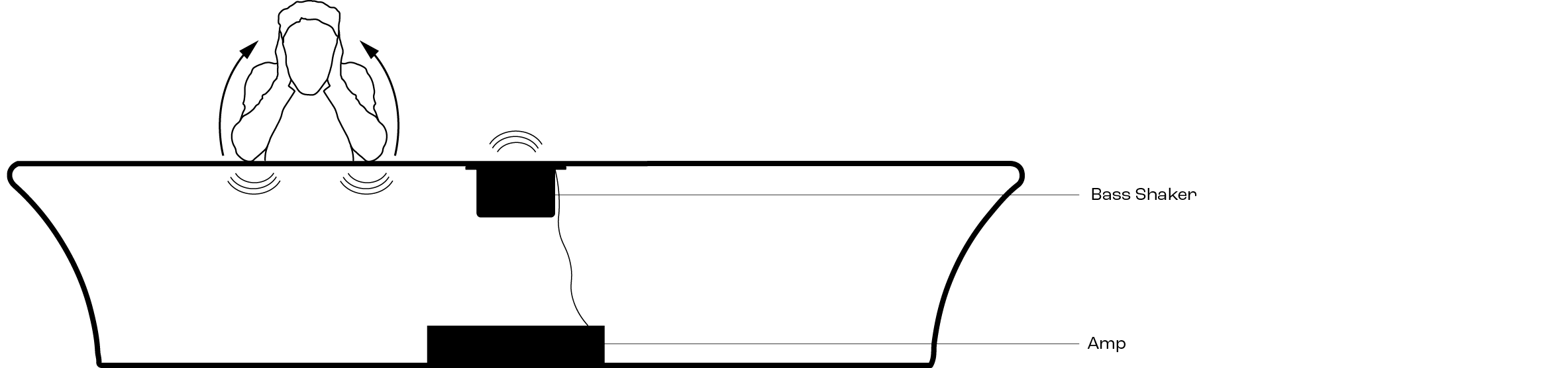

Touch

The physical vibrations of the instrument encourage visitors to touch the surface and feel the motion of the ground. Bone-transducing touch-points close to the ears, like elbows, are ideal to hear and feel the vibrations as they move through the human body.

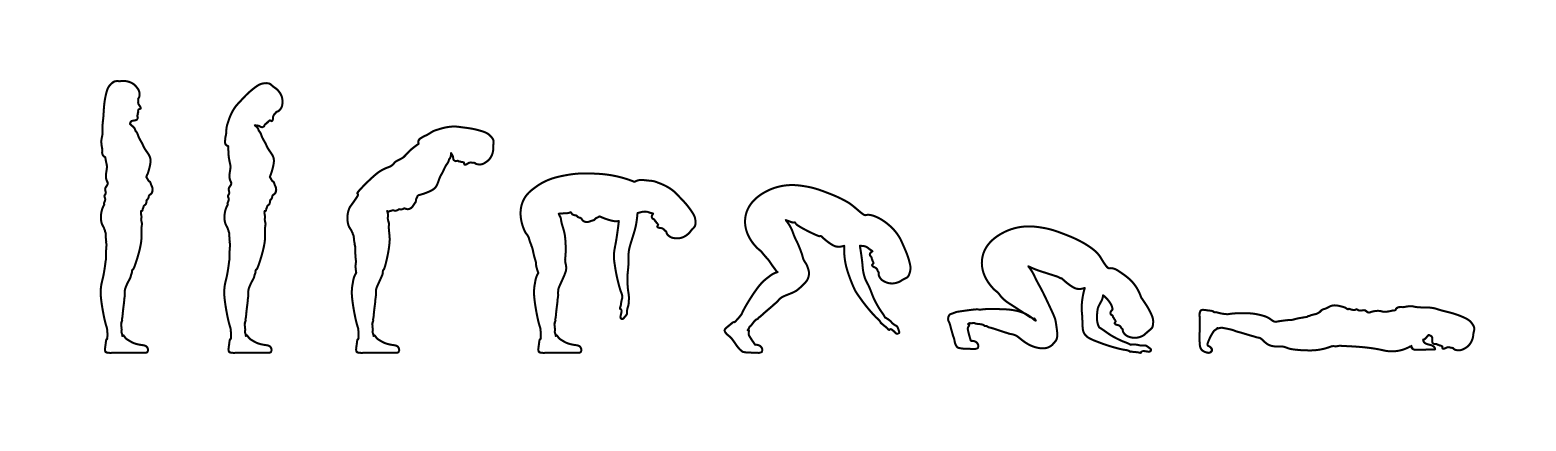

Prostration

Visitors can kneel next to the instrument with elbows placed on the surface or lie on the surface to feel the sound, moving from an upright position to one similar to religious prostration.

The construction consists of an oxidized steel base and platform that encases a bass-shaker and amplifier. The bass transducer is attached to the top surface from inside the steel case. The rusted patina of the reclaimed steel blends into Yellowstone’s textured landscape.

Bibliography

Albuquerque Seismological Laboratory (ASL)/USGS (1990): United States National Seismic Network. International Federation of Digital Seismograph Networks. Dataset/Seismic Network. 10.7914/SN/US

Benson, C., Watson, P., Taylor, G., Cook, P., & Hollenhorst, S. (2013). Who Visits a National Park and What do They Get Out of It?: A Joint Visitor Cluster Analysis and Travel Cost Model for Yellowstone National Park. Environmental Management, 12.

Fuchs, J. (2017). Ultrasonics - Sound - Effect of Speed of Sound on Wavelength. Retrieved from https://techblog.ctgclean.com/2011/10/ultrasonics-sound-wave-length-vs-frequency/

Heintzman, P. (2009). Nature-Based Recreation and Spirituality: A Complex Relationship. Leisure Sciences, 32(1), 72–89.

Kulesza, C., J. Gramann, Y. Le, & S. J. Hollenhorst. (2012). Yellowstone National Park Visitor Study: Summer 2011. Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/EQD/NRR—2012/539. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado.

Albuquerque Seismological Laboratory (ASL)/USGS (1990): United States National Seismic Network. International Federation of Digital Seismograph Networks. Dataset/Seismic Network. 10.7914/SN/US

Benson, C., Watson, P., Taylor, G., Cook, P., & Hollenhorst, S. (2013). Who Visits a National Park and What do They Get Out of It?: A Joint Visitor Cluster Analysis and Travel Cost Model for Yellowstone National Park. Environmental Management, 12.

Fuchs, J. (2017). Ultrasonics - Sound - Effect of Speed of Sound on Wavelength. Retrieved from https://techblog.ctgclean.com/2011/10/ultrasonics-sound-wave-length-vs-frequency/

Heintzman, P. (2009). Nature-Based Recreation and Spirituality: A Complex Relationship. Leisure Sciences, 32(1), 72–89.

Kulesza, C., J. Gramann, Y. Le, & S. J. Hollenhorst. (2012). Yellowstone National Park Visitor Study: Summer 2011. Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/EQD/NRR—2012/539. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado.

Marsh, P. E. (2008). Backcountry Adventure as Spiritual Development: A Means-End Study. Journal of Experiential Education, 30(3), 290–293.

Meyer, J. L. (1994). The permanence of place: the enduring spirit of Yellowstone National Park.

Mings, R. C., & Mchugh, K. E. (1992). The Spatial Configuration of Travel to Yellowstone National Park. Journal of Travel Research, 30(4), 38–46.

Ostrom, E. (2009). A General Framework for Analyzing Sustainability of Social-Ecological Systems. Science, 325(5939), 419–422.

Ross-Bryant, L. (2005). Sacred Sites: Nature and Nation in the U.S. National Parks. Religion and American Culture, 14(1), 31–62.

University of Utah (1983): Yellowstone National Park Seismograph Network. International Federation of Digital Seismograph Networks. Dataset/Seismic Network. 10.7914/SN/WY

Special Thanks

Jeff Moore, University of Utah Geology Department

Milad H. Mozari, Multi-disiplinary Design, University of Utah.